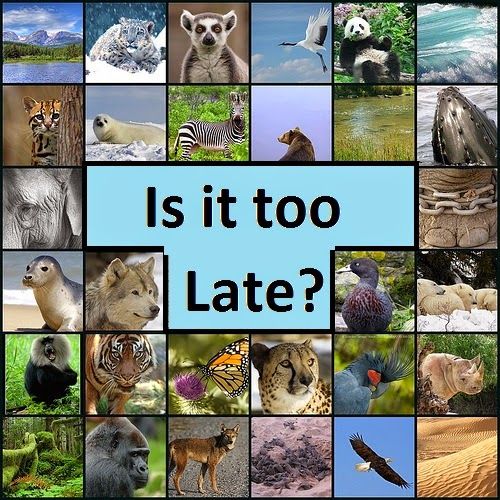

Continued from last week, this week we count down from 5 to 1.

5. Tooth-billed Pigeon

A relative of the extinct dodo, tooth-billed pigeons are disappearing at an alarming rate. They only live in Samoa and are currently fewer than 400 left in the wild, with no captive populations to help conservation efforts. They are elusive birds, very rarely seen. Even though illegal today, hunting has played a huge part in their decline, along with the main threat being habitat loss due to agriculture, or natural causes likes cyclones or trees.

4. Gharial

Gharials are fish-eating crocodiles from India. They have long thin snouts with a large bump on the end which resembles a pot known as a Ghara, which is where they get their name. They spend most of their time in freshwater rivers, only leaving the water to bask in the sun and lay eggs. There are only around 200 left in the wild. Their decline is due to several issues, though all human-made. Habitat loss, pollution and entanglement in fishing nets pose as some of the biggest threats.

3. Kakapo

The kakapo, also called owl parrot, is a species of large, flightless, nocturnal, ground-dwelling parrot. The total known adult Kakapo population is 209, all of which are named and tagged, confined to four small islands off the coast of New Zealand that have been cleared of predators. A kakapo’s natural reaction is to freeze and blend in with the background when threatened. It is effective against predators that rely on sight to hunt but not smell.

2. Amur Leopard

Amur leopards are one of the world’s most endangered big cats. They are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In 2015, there were only around 90 Amur leopards left within their natural range. That number is now estimated to be less than 70. Like all species on the endangered list, humans are their biggest threat. Their beautiful coats are popular with poachers as are their bones which are sold for use in traditional Asian medicine. They are also at risk from habitat loss due to natural and human-made fires.

1. Vaquita

The vaquita is both the smallest and the most endangered marine mammal in the world. It has been classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN since 1996, and in 2018, there were only around 15 vaquitas left. The latest estimate, from July 2019, suggests there are currently only 9. Their biggest threat is from the illegal fishing of totoaba, a large fish in demand because of its swim bladder. Vaquitas accidentally end up entangled in the gillnets set for totoaba and drown because they can no longer swim to the surface to breathe.

This is the introduction to a series on animals that are endangered or in decline, giving them a name so that we can give them a voice.

A.E. (Anthony) Lovell

The death of hundreds of elephants in Botswana has been an unsolved mystery for a long time during this pandemic in Botswana. Most of these have shown the symptoms of dizziness and walking in circles before dropping dead face-first. Government officials quote that 281 elephants have been verified to be dead with this bizarre behavior, but the conservationists and the NGOs claim that the death toll is much higher.

Initially, wild life experts have omitted the possibility of tuberculosis and believe that the cause is beyond the known diseases. Though the death number does not sound serious in population perspective, it is absolutely critical to complete the diagnosis and have accurate results in order to avoid any foul play or before elephants succumb to more of such mysterious deaths.

Botswana has an estimated 130,000 Savanna elephants and is considered to be one of the last strongholds of species in Africa. The earlier estimations were to be around 350,000 and ivory poaching in 20th century has reduced the species to one third of them today. The thousand-square-mile to the northeast of Okavango Delta, which has witnessed the deaths of elephants has around 18,000 elephants roughly. The wildlife experts and veterans believe that the possible causes could be the ingestion of toxic bacteria into the water, viral infection from rodents in the area or a pathogen infection. Conservationists are also considering the possibility of poisoning by humans.

The investigating officials of the Botswana government had sent for the testing to the laboratories in Zimbabwe, South Africa, US and Canada as well. The wild life department made a press release that the deaths are probably due to natural toxins.

However, the officials have confirmed that the conclusion could not be made about the cause yet. Authorities have so far ruled out anthrax, as well as poaching, as the tusks were found intact. They believe that some bacteria can naturally produce poison, particularly in stagnant water.

Elephants Without Borders (EWB) is a wildlife conservation charity that first flagged about these mysterious deaths. Their confidential report with references to 356 dead elephants was leaked to the public media in early July. The charity suspected that the deaths were not restricted to any specific age group or gender and has also highlighted that many live elephants have shown signs of weakness, lethargy and even disorientation.

Presence of green lush vegetation and the fact that waterholes in the vicinity are still full of rainwater eliminates the possibility of deaths due to dehydration or starvation. Though the blue green algae can be deadly when consumed along with water, elephants generally drink water from the middle of the water bodies, but not edges. But there has been a pre-historic mass elephant deaths due to Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) and this cause could only be substantiated with the laboratory results, which is still underway. The neurological symptoms like walking in circles suggests that anthrax poisoning is also a possibility.

The Anthrax bacteria occurs naturally in soil and elephants become infected if they have ingested contaminated soil or breathed in. Anthrax is known to be affecting wild life and domestic animals around the world.

Experts opinionated that it requires a detailed sampling of carcasses, soil and water in the delta area for an accurate explanation. But the challenge is the remoteness and the hot weather in the area which could have degraded the body, erasing important evidences, and scavenging animals which may eat organs making it extremely challenging for the examination. Despite the wildlife conservationists’ huge cry worldwide, there is still no confirmation on the absolute cause for the hundreds of elephant deaths.

Marabou stork is a large, unusual-looking bird. In addition to hollow leg bones, marabou storks have hollow toe bones. In such a large bird, this is an important adaptation for flight. The African Marabou storks reach a wingspan of 2,6 m and a height of 1,5 m.

Marabou stork is a large, unusual-looking bird. In addition to hollow leg bones, marabou storks have hollow toe bones. In such a large bird, this is an important adaptation for flight. The African Marabou storks reach a wingspan of 2,6 m and a height of 1,5 m.

Marabou storks are bald-headed. Males can be identified by their large air sacs. In addition, males are generally slightly larger and taller than females. Sexes are alike in coloration. A juvenile has similar coloration but is duller. Immature birds have a woolly covering on their heads and do not gain the black in their plumage until about three-years-old.

Its soft, white tail feathers are known as marabou. Its neck and head contain no feathers. The Marabou stork has a long, reddish pouch hanging from its neck. This pouch is used in courtship rituals. The naked 18-inch inflatable pink sac is particularly conspicuous during the breeding season. It connects directly to the left nostril and acts as a resonator allowing the bird to produce a guttural croaking. While usually silent, the Marabou Stork will also emit a sound caused by beak clacking if it feels threatened.

They mainly feed on carrion and scraps. Although it doesn't seem to be very sympathetic in human eyes, this behavior is of great importance to the ecosystem they inhabit; by removing carcasses and rotting material, Marabous help to avoid the spreading of pathogens. They are scavengers, they eat anything from termites, flamingoes and small birds and mammals to human refuse and dead elephants. They also feed on carcasses with vultures and hyenas.

Marabou storks are attracted to grass fires. They march in front of the advancing fire grabbing animals that are fleeing.

Marabous breed on the treetops, where they build large nests. It reaches sexual maturity when it is approximately four years old and usually mates for life. They are colonial breeders, their nests are a large, flat platform made of sticks with a shallow central cup lined with smaller sticks and green leaves. Usually, 2-3 eggs are laid during the dry season. Both sexes incubate; eggs hatch in 30 days. Their young are helpless at birth. Both sexes tend and feed the young. The fledging period is 3-4 months.

Marabou Stork defecates upon its legs and feet. It helps in regulating body temperature, and also gives the false appearance that the birds have lovely white legs. Like many birds, the Marabou Stork also pants when it becomes hot, again to lower its body temperature.

These are particularly lazy birds and spend much of their time standing motionless, though once they take flight they are very elegant, using thermal up-draughts to provide the needed lift. Like other storks, they fly with their especially long legs trailing behind, but unlike their cousins they keep their neck tucked well in and bent into a flattened S; this allows the weight of the heavy beak to be taken on the shoulders. #birdsofeastafrica.

The white ring around the waterbuck’s hindquarters has led to many tales. A favorite is that they were the first animals to use the toilet on Noah’s Ark. The newly-installed toilet seats on the ark were still wet with paint and left a distinctive white ring on their rumps. Despite these bucks being a part of the ‘butt joke’, there are valid reasons for the white markings on their hindquarters. Flashes of color often scare off predators and act as a ‘follow me’ sign, helping other waterbucks flee when in danger.

The white ring around the waterbuck’s hindquarters has led to many tales. A favorite is that they were the first animals to use the toilet on Noah’s Ark. The newly-installed toilet seats on the ark were still wet with paint and left a distinctive white ring on their rumps. Despite these bucks being a part of the ‘butt joke’, there are valid reasons for the white markings on their hindquarters. Flashes of color often scare off predators and act as a ‘follow me’ sign, helping other waterbucks flee when in danger.

Waterbuck are sexually dimorphic, meaning males and females have external differences apart from their reproductive organs.

Males can be up to 25% larger than their female counterparts and they carry the defining feature of beautiful, long, ringed horns.

These horns curve backward and then forward and vary in length from 55 cm to 99 cm. The age of the bull determines the length of the horns.

Waterbuck horns will begin to develop at around 8 to 9 months and mark the young buck’s time to separate from the herd. Young males form bachelor groups remain together until they mature and move on to make their own herd. Waterbucks’ diets are rich in protein and other nutrients. This includes coarse grasses that are seldom eaten by other plain animals and long sweet grasses like buffalo grass.

During the dry season, they supplement their diet by browsing on leaves from shrubs and certain trees, such as the Sweet thorn (Vachellia karroo). At times, you will find them shoulder-deep in water, eating roots and other aquatic plants.

They also enjoy browsing on certain fruits, especially the marula fruit during the ripe season. These antelope typically eat in the mornings and late afternoons and chew cud for the remainder of the day.

These herbivorous animals have remarkably high water requirements. They need to drink often, which is one reason why they remain close to permanent water points at all times. You’ll often find them nestled in reed beds near rivers and dams, or on floodplains.

Common waterbuck are social animals. They live in herds or groups of up to 12. Male antelopes are dominant over a certain territory, and their herd consists of females, young bachelors, and calves.

The herds are constantly changing, as individuals can join or leave at any time, provided there aren’t other males looking to dominate the territory.

When a bachelor threatens the territory of a herd leader, the dominant male will posture aggressively and even start a fight if necessary. These fights can be fatal, as the waterbuck uses its long, strong horns in combat.

Typically, a waterbuck will live up to 18 years in the wild. In general, 12-15 years is a good life for a wild waterbuck. @GodfreytheGuide #Antelope #https://www.instagram.com/p/CQo-ZP4gIwZ/?utm_medium=copy_link